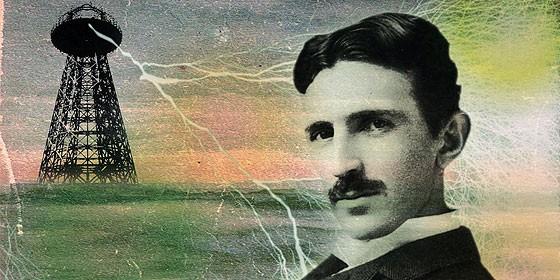

Last month’s issue described our Section’s participation in the Tesla 160th birthday celebration held on the grounds of his Wardenclyffe laboratory in Shoreham. The event was organized by the Tesla Science Center which will be housed in the Tesla Laboratory in the future. I indicated that four of our IEEE members spoke about aspects of Tesla’s life and his inventions. The first talk was given by me and is reprinted below. The texts of the other three talks will be published in subsequent Pulse issues.

What Electrical Engineers Can Learn From Tesla

Studying Tesla’s patents and technical papers, while over 100 years old, can be beneficial to today’s electrical engineers. Time limits allow me to give only two examples.The first is his invention of the induction motor which was described in a paper presented at an AIEE meeting in May of 1888.* The AIEE merged with the IRE to become the IEEE in 1963. The title of Tesla’s paper was “A New System of Alternate Current Motors and Transformers.” It described his invention of the AC induction motor. It quickly caught on and was extensively used in industry and home electrical appliances. What struck me the most was that he described his brilliant invention in great detail and used almost no mathematics. It is an excellent example of how an inventive mind could visualize things working without the need for design formulas. While engineers today rely on computer simulation for their design, he was able, with a strong intuitive gift, to overcome the lack of design tools. The lesson that I took away from this is that, as good as our CAD is today, we still need to cultivate the ability to picture in one’s mind a working concept before going through a computer simulation process.

The second example is his experiments with wireless power transmission. Tesla became convinced that he could transmit electrical power without wires over long distances and possibly around the world. He did experiments at Colorado Springs and then at Wardenclyffe in the early 1900’s.

While the idea was not demonstrated, we should not lose sight of his ability to conceive great things that might work, was a very special gift. For example, his idea of sending wireless power is finding application in medical devices, such as cardiac pacemakers. They can now be recharged via wireless means, thereby eliminating the need for replacement operations. Helicopters have been experimentally demonstrated to stay in the air as long as possible by getting their power from ground-based microwave beams. The point is that the original idea may fail, but it can live on in a different form.

There are lessons to be learned from these examples for today’s engineers:

• Think big. You want ideas that can have significant benefits to society and try first to look at your ideas conceptually before getting mathematical.

• Your idea may not work just because you like it. It is essential to model its performance using the appropriate theory and CAD tools.

• If the modeling is successful, you can then proceed to construct prototypes.

• If the modeling is unsuccessful, do not throw the idea out immediately. Sometimes a minor variation could lead to success. Keep trying as long as your reasons for continuing are rational.

• You should also consider more modest applications. For example, by limiting wireless power transmission to shorter distances, other inventions could materialize.

While today’s engineers rely heavily on design software, a study of Tesla’s brilliant approach to big problems will show that there is much to learn from him that has passed the test of time.

* This paper can be accessed from IEEE Explore. It was reprinted in the February 1984 issue of the Proceedings of the IEEE on pages 165-173.